As we get closer to the Young Israel synagogue in the prestigious Upper West Side neighborhood of Manhattan, the journalist next to me pulls out his kippa from his pocket, and places it in a smooth, natural motion on his head. Then, he places his cellphone up against the monitor beside the door. Following the increase of Antisemitic incidents across the United States, he explains, the synagogue has been equipped with advanced security devices, and entry is only permitted to those who have a unique ID barcode. As we cross the doorstep I can’t help but think: who would have thought I’d be davening Mincha with Peter Beinart.

The New Yorker recently described Beinart as “the most influential liberal Zionist of his generation,” adding he “had switched sides.” Today he is viewed as a harsh critic of the State of Israel, a supporter of the BDS (Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions) movement, and one of the most hated people in America’s organized Jewish world. And yet, here we are. Because Beinart is also an Orthodox Jew, and for the past year he has taken pain to pray with a minyan three times a day as he says Kaddis in his father’s memory.

Minutes before, while at a burger restaurant a few blocks away, the only thing we could agree on was what to order from the menu. The reason we had met was my attempt to understand why the Jewish Progressive movement in the US – of which Beinart is a prominent voice – is constantly increasing its negative attitude towards Israel, and what might halt this disturbing trend.

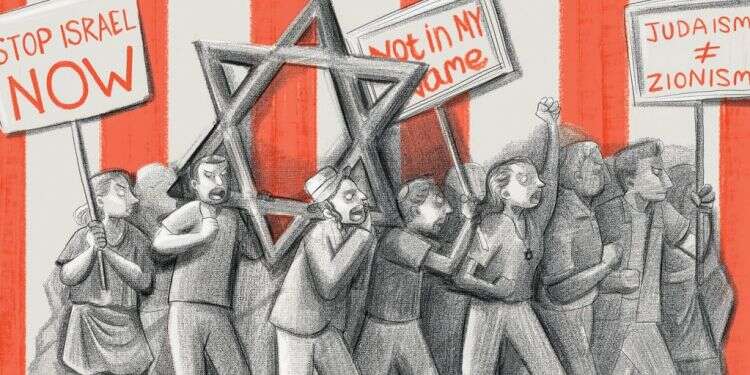

It was easy to see the effects of the anti-Israel radicalization around the May escalations between Israel and Hamas, when the pro-Palestinian demonstrations across the US attracted a number of Jewish organizations. During those days, Beinart wrote an essay in Jewish Currents in which he claimed: “If Palestinians have no right to return to their homeland, neither do we.” Two days later Congresswoman Rashida Tlaib, a woman of Palestinain descent identified with the far Left of American politics, quoted him. At the same time, Zionist influencers began tweeting against him and his writings using a special hashtag: #BeinartPogroms.

“The time of military conflict was awful,” Beinart says. “Though I have never lived in Israel for a long period of time, during one of the previous rounds of fighting I was with my daughter in a bomb shelter. I know many people who were affected by these incidents, and I worried for them – but I also worried for many of the Palestinians I know.”

You express your concern for Israelis and Palestinians in the same sentence, without distinction. From a Jewish perspective, this is worrying.

“Without a doubt, there is a difference; I have a special obligation to the Jews,” Beinart answers slowly, carefully choosing his words. “I’m not a pure universalist, I believe in Jewish Peoplehood; Jews all over the world are my distant relatives. I also believe in the covenant of faith described by Rabbi Soloveichic, according to which you have an obligation to every Jew in distress – otherwise you violate your own Judaism. I believe in that. But I also believe the Palestinans are suffering more than the Israelis. If for every Jewish child killed five Palestinian children die, then, to me, it’s the same as something bad happening to my relative and at the same time something much worse happening to the neighbor at the end of my street. That’s how I see things.”

Calls heard at anti-Israel demonstrations were nothing less than Antisemitic.

“The claim of Antisemitism existing within the American pro-Palestinian movement is not correct. I won’t say there is no Antisemitism from the Left, but it is smaller than what those on the Right claim. Defining Israel as an apartheid state is not Antisemitism, and neither is anti-Zionism.”

The International Holocaust Remembrance Allience (IHRA), which has 36 member states, states that challenging the right of a Jewish state to exist is Antisemitism. You don’t accept this?

“No. To me it’s an absurd definition. If I don’t believe in a Jewish state and the legitimacy of Israel, if I want there to be a boycott against Israel – and there are many Jews who think and act accordingly – why is it Antisemitic? Most people who claim the pro-Palestinian movement is filled with Antisemitism don’t see the movement from within.”

Beinart then quotes a paper by TUFTS university, “which showed the opinions about Israel among the radical American Left is very negative, but also found among them less forms of classic Antisemitism. There is a significant difference between their view of Israel and their opinion of Jews.”

Do Jews in the radical Left view themselves as Zionists?

“The majority do not.”

And you?

“I’m a cultural Zionist.”

What does that mean?

“Ehad HaAm, for example, didn’t believe in a Jewish State, and neither did those who followed in his path – Martin Buber, Yehuda Leib Magnes and others. They believed in a Jewish society which didn’t have to be constructed like a state. I also believe in that. Not in a Jewish State, yes in the importance of a Jewish society in Israel, which can flourish in ֵa state of all its citizeֵns [a state that has no Jewish national significance but is completely equal in its citizens’ rights, Z.K.] or a federation which gives equal rights to all. The Jewish People need a place, but there doesn’t have to be a Jewish State.”

There are Muslim countries, so why not a Jewish one?

“If you believe in equality, how can you create a State which claims members of a certain race, or certain religion, belong to it more than others? True, there are other countries who violate this principle. In my opinion, they need to be reformed.”

So why do young Jews from the radical Left not take to the streets to demonstrate against Syria or Iran – countries violating human rights in the worst possible way? Why only demonstrate against Israel? Because they’re Jewish?

“As Americans, we don’t provide $3 billion in military aid to Iran or Syria. Asad is a monster, and we are his enemies – as we should be. But without us, Israel couldn’t do everything it does.”

Nostalgic Choulant

As a journalist covering American Jewry – the largest Jewish community outside of Israel – for over a decade, I am exposed to quite a few research papers and essays about the younger generation there. It turns out it is not only drifting apart from Israel, it is also acting to turn the public opinion around the world against it. In 2014, for instance, a new organization was created to challenge the organized Jewish-American community – IfNotNow. The group’s activists, who call to end “Israel’s military rule over Palestinians in the West Bank, East Jerusalem, and Gaza,” organize demonstrations against American politicians and Jewish institutions, and blame them for supporting the occupation. These aren’t outliers or ‘stray weeds.’ They are the product of the Jewish-American educational system, summer camps and the very best Reform and Conservative private schools. While the organization does not have very many members, it is snowballing and gaining more traction among young people who grew up in homes were being pro-Israel was a given.

Such opinions are becoming more popular. A recent survey found 22 percent of young Jews think Israel is ethnically cleansing the Palestinians; 25% agree with the saying ‘Israel is an Apartheid State.’ Also among those who oppose these statements, many don’t view them as Antisemitic.

One of those fighting these trends is Liel Leibovitz, a senior editor at Tablet – a conservative, Jewish magazine. This round was different, because “once and for all, it opened up a chasm that many of us have spent our lifetimes trying to avoid. Simply put, there are only two sides now: the Zionists and the anti-Zionists. Given the events of this past week, it is incumbent upon every person who wants to have any effect on the future, Jew and non-Jew alike, to understand how and why this is—and to pick a side, and soon.,” Leibovitz wrote during the most recent round of conflict. “There are only two camps that will have any political significance in the coming decade. In the first are the people willing to call themselves Zionists—without clarification or caveat or distinction,” he added, calling the violent anti-Jewish attacks in Los Angeles which occured at this time period “pogroms,” and explained their purpose was to attack Jews as revenge for Israel’s actions.

“Today’s progressive ideology is religiously-fanatic, oppressive and total,” Leibovitz tells me. “The moment you open the door for them and adopt their terminology – you’re done for. It is a new religion which is morally opposed to Judaism. There isn’t a single Jewish institution that hasn’t dealt with the progressive threat.”

I meet with Leibovitz in his Upper West Side apartment, which is a good indicator of his unusual character. The home is filled with endless shelves filled with an infinite amount of books, and in the middle is a two-shelved cart with alcoholic beverages. “We’re a home with some people who keep Kosher – that’s me – and some who don’t,” he says as he directs me to the bottles which meet the Jewish-religious criteria.

He’s 45-years-old, married to author Lisa Ann Sandell, and a father of two. He immigrated to the US twenty years ago, but still doesn’t have American citizenship. Originally he’s from Tel Aviv, son of Roni Leibovitz – known in Israel as the ‘Ofno-Bank’ – who robbed 21 banks over the course of 1989-1990. He graduated high school and served in the IDF’s Spokesperson unit while his father completed his prison sentance. After his time in the army, he completed his under-grad studies in film and cinema at the Tel Aviv University, and his Masters in journalism and Ph.D in communications at Columbia University, NYC. He worked as the spokesperson for the Israeli consulate in the city, was the culture editor for the NY-based Jewish Week, and wrote for other papers, including the New Republic. In recent years, alongside his writing for Tablet, he is a co-host of the most popular Jewish podcast in the US, and maybe the world: UnOrthodox. His seven books deal with a wide range of topics, from moving to Israel, through Leonard Cohen’s life, to the religious experience you can get from computer games.

Alongside his career as a journalist, Leibovitz embarked on an academic career, and was given tenure at NYU. Then, however, he made his big mistake and asked to join a forum of university faculty who would meet on a regular basis to discuss the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Leibovitz thought they would be interested in hearing him, a non-observant Jew who grew up in Israel, voted for the Left Wing Meretz party and defines himself as a Zionist. To his surprise, he was told his views were “outside the legitimate boundaries” of the conversation, and he would not be able to participate in the conversation. Leibovitz decided to fight back – a decision which resulted in NYU canceling his tenure. Since then, he underwent what he calls a “process of sobering up” which included shifting to the positions of the Israeli and American Right, as well as taking upon himself more religious aspects of Jewish life. Today he also hosts a podcast on Tablet where he discusses passages from the Talmud, the cannonic Jewish text.

“I’ve made my choice—reluctantly and mournfully at first, but I’m starting to feel some measure of hope and excitement,” he wrote in the essay, which is titled “Us and Them.” If you join my side, know that you may find coworkers, friends, and maybe even family members going the other way. The fear and pain you feel—about having to choose at all, about the loss of nuance, about the corrosion of so many institutions you once loved and trusted, about the betrayal of so many who once felt like your friends, about the violence all around you, about how depressing it all feels right now—is real. There’s no easy way, perhaps no way at all to avoid any of this, which is a terrifying realization.

Leibovitz’s essay made waves among the American Jewish community, as it asked what is happening to Jewish life in the US. “In liberal and non-Orthodox circles, individuals and institutions that devote most of their emotional and spiritual energies to checking off the rapidly shifting boxes erected by the left are going to find themselves with a version of Judaism mostly disconnected from religious observance, and which will therefore attract only the people in the market for progressive activism, with a little bit of cholent thrown in for nostalgia’s sake,” he writes, adding, “this is a tiny minority. So while this strategy may be the key to success for some institutions, it will be short-lived: No one wants to schlep to shul to be lectured to endlessly about white supremacy or gender spectrums. Why? Simple: because you can get better versions of it elsewhere. People who sought out those spaces for meaning and community and spiritual inspiration will just start to stay away, as studies suggest they already are.”

In the Progressive parts of US Jewry it’s harder and harder to live a Jewish life, especially as a Zionist, Leibovitz tells me. “The moment a large minority says it is unwilling to see an Israeli flag in any place in the community building, because Israel is an apartheid state, I say – we have nothing left to talk about.” His emotions show as he explains: “It’s ‘Us’ and ‘Them,’ and it’s time to choose. Are you with us or against us?”

What do the ‘Them’ Jews hear in Synagogue hear? What is the dominant discourse there?

“Rabbinical students come to them and give a sermon about ‘Black Lives Matter’ (BLM) and ‘Tikkun Olam.’ The people sitting in the audience – some of them smart and wise – say to themselves that it sounds good. Tolerant. Progressive. ‘Let’s adopt it,’ they think. At that moment an entity competing with Judaism is formed, one different that original Judaism and hostile towards it – and then the inner-communal fighting start.”

Why do their progressive views and concern for minorities go hand in hand with anti-Israel ideas?

“Israel scares the progressives because it is a country with basic ideas of community, family and faith. It is against their values,” Leibovtiz says calmly. “This is why no matter what Israel society does, or how open and accepting it will be – the principle bothers them. To them, when Israel acknowledges and adopts LGBTQ rights it’s merely an act of ‘pinkwashing,’ aimed at hiding crimes against humanity. It’s absurd. To them, reality means nothing. You can’t even say ‘I don’t like Netanyahu’s policies, but as a Gay couple of men or women we can enjoy living in Israel without fear.’ Extremism doesn’t allow for other opinions to be heard.”

About a quarter of American Jews, he notes, are Orthodox – from the ultra-Orthodox through to the most liberal of the modern Orthodox. Most of them unequivocally support Israel. “About This 60% of American Jews are confused and detached from institutional Jewish life, so they also don’t know where they stand regarding Israel. The number of people praying in Reform and Conservative synagogues is decreasing dramatically, as is participation in JCC activities,” Leibovitz explains. “It’s a great place to play tennis – but the question is if there’s anything beyond that.”

Lecture invitations stopped coming

The progressive religion Leibovitz talks about materialized before my eyes a few days later. As part of my work, I was filming a video for the Makor Rishon newspaper, and joined a demonstration by ‘Queers for Palestine,’ where activists drew a line between Palestinian rights and LGBTQ rights. Under the pretence of filming a documentary, I asked demonstrators if you could openly live as gay in under the control of the Palestinian-controlled West Bank or in Gaza. “Yes, you can even marry a same-sex spouce,” one of them told me. When I asked if they had heard the IDF prevented a pride parade from happening in Gaza, they answered in the affirmative. “It’s an awful thing. It only shows how Israel deprives basic rights.”

Many Jews were present at the demonstration, some of them with horrific statements. In the name of ‘Tikkun Olam – which one had tattooed on his neck – they called for individual rights which don’t exist under the rule of the Palestinian Authority or Hamas. The slogans coming from their throats made me realize someone was using their ignorance to tarnish Israel’s face.

“Looking at American history you see that all the great fighters for human rights, like Abraham Lincoln and Martin Luther King, all were connected to the moral and conceptual ideas planted in the vision of the Israeli prophets” in the Bible, Leibovitz says. “You can’t understand King without understanding the passages he quotes from the Bible. Today, when you talk about ‘Justice’ you’re not quoting the book of Isiah. Moreover, to them alluding to the Bible is a terrible thing.”

Leibovitz and Beinart live in the same neighborhood, and send their children to the same Jewish school. In their religious beliefs, they both combine an Orthodox approach with liberal values. Yet, the ideological difference between them seems unbridgeable. The 50-year-old Beinart started working as an editor in the prestigious New Republic magazine in the 1990s, and at age 28 was its editor in chief. Later he was the senior political correspondent for the Daily Beast, and his pieces have been published in Time Magazine, the New York Times, The Forward and the Atlantic, to name a few. Today he teaches journalism and political science at the City University of New York (CUNY), and is a senior editor of the Jewish Currents magazine and website, an outlet heavily identified with the progressive Jewish Left. He has a B.A in history and political science from Yale University, and an M.A in international relations from Oxford University.

For many years, Beinart was considered an enthusiastic supporter of the two state solution. However, in recent years he started to object – and not because he became an extreme right winger. In his writing he explained that he was leaving the Zionistic Left’s vision and choosing a single, bi-national state solution. “I no longer believe in a Jewish State,” he wrote in the NY Times. In a long piece in Jewish Currents he explained that many Jews look at the world through an outdated “Holocaust lense,” which is why they think a sovereign Jewish State is needed – to prevent a second Holocaust. “Ever since the Holocaust, Jews have retroactively projected Nazism’s exterminationist program on Palestinian opposition to pre-state Zionism. But this Holocaust lens distorts how Palestinians actually behaved: not like genocidal Jew-haters, but rather like other peoples seeking national rights.”

Beinart’s support of the single state was highly influenced by Ali Abunimah, a Palestinian-American journalist and political activist, one of the heads of the BDS movement. “Ali Abunimah's book, One Country, which is both trenchantly argued and deeply generous in spirit. I wish I could assign it in every Jewish school,” he tweeted. The content of this book, or other pieces by the man Beinart praised so highly, would make any Zionist shudder. Abunimah objects to “Jewish control in the Land of Israel,” and Zionism is, to him, “a dying project in withdrawal, finding it hard to recruit new supporters.” He constantly compares Israel to Apartheid-era South Africa, and sided with a British politician who likened Israel to Nazi Germany. Asked if, in negotiations, the Palestinians should acknowledge Israel’s right to exist, Abunimah replied the Palestinians could “never give legitimacy to an entity which saw natural population growth an existential threat.”

In the summer of 2018 Beinart arrived in Israel to celebrate his daughter’s Bat Mitzva. Upon arrival at Ben Gurion Airport, he was taken aside for questioning, probably because he was suspected of advancing the BDS. He later said the guards questioned him about his political views, his participation in a demonstration in Hebron, about groups inciting to violence and “groups that threaten Israeli democracy.” The Prime Minister’s Office issued a statement saying it was an “administrative error,” and Beinart replied on Twitter: “I’ll accept when he apologizes to all the Palestinians and Palestinian-Americans who every day endure far worse.”

Even though most American Jews vote for the Democratic Party – and maybe because they do – the mainstream of the Jewish Left are furious at the journalist who moved as far as the extreme ideological areas of Senator Bernie Sanders. On the one hand Beinart represents a growing portion of American Jews; on the other, Jews from the Right, and also Center-Left, have begun to view him as unwanted. He says there are few synagogues that will invite him to give lectures today; large Jewish bodies, which used to host him on a regular basis, have decided over the past few years to sever any and all ties with him.

He doesn’t only criticize Israel, but also the established American Jewish institutions and organizations. In a piece from January 2021 Beinart wrote: “The American-Jewish establishment claims denying a state from the Jews hurts their right for national self-determination. They’re wrong […] the Biden Administration needs to decide whether to accept the Jewish establishment’s claim that opposing a Jewish state is Antisemitism.”

Palestinian text books ignore Israel’s existance in the good case, and in the worst one portray it from an Antisemitic perspective. Also there you don’t see a problem?

In response, Beinart refers to a joint American-Israeli-Palestinian research: “The researchers compared Palestinian and Israeli text books, and didn’t find a difference. In both there is only one narrative.”

This isn’t about a narrative. Palestinian books have caricatures of Jews with big noses, beards and weapons, butchering children. How can you have a conversation with people who have been brainwashed like that?

“If you ask a Palestinain were his hostility comes from, he’ll share a personal story about his parents who were expelled or family member who was shot. Here you don’t need a textbook, it’s their personal experience.”

And still, I ask Beinart, why don’t we hear from organizations like IfNotNow, who demonstrate for the Palestinians, a little empathy towards the Israeli side, to whom they should feel a connection, as Jews. “A group like IfNotNow is a good example of Jews who care about other Jews. Most of the young American Jewish are worried more about climate change or the threat to American democracy – because they hear a party saying any administration elected with the votes of blacks or browns is illegitimate,” Beinart hints at the Republican Party. “They have so many issues to be concerned with, yet they still engage with what’s happening in the Middle East. That stems from a connection. I look at the conflict as a situation in which my family member is doing something terrible. I think this is also their point of view.”

Why don’t they treat Hamas as a terror organization making Palestinians’ lives miserable?

“I don’t know how many Palestinian friends your readers have, but some of the Jewish-American children you’re talking about are in close relationships with Palestinians here in the US. If their friends don’t tell them the bigger problem in the conflict is Hamas – they won’t think that. And I’ll add, that every Palestinian I know thinks Hamas are a bunch of idiots, and Mahmoud Abbas is an idiot.”

So why don’t their Jewish friends say it out loud?

“They believe the core problem is that the Palestinians are under the occupation of a Jewish State, and the Israel controls Gaza and prevents basic human rights.”

Things we didn’t learn at Camp

Most young American Jews who see Israel as the embodiment of all evil in the world, I tell Beinart, belong to the progressive part of the American community. Through my eyes – someone who reads American papers and talks to many American Jews on a weekly basis – it seems like anti-Israel has become their religion. “I don’t think it’s fair to phrase it that way,” Beinart says. “You wouldn’t want me to draw a caricature or talk about the Israeli national-religious population in stereotypes.”

Usually I’m not a very opinionated person, and there aren’t many discussions where I loose my calm, but all of a sudden, in this argument, I found myself banging the table. We are looking at youngsters who take every Jewish value and turn it to the Palestinian side, I tell Beinart. Judaism has Kadish? So they say it for Palestinians who died, sometimes even Hamas terrorists. Passover Seder? Dedicated to the redemption of Palestine. To them the only value in Judaism is ‘Tikkun Olam,’ what else do they have?

“With all due respect, you see it from far away,” Beinart says. “It is true the Orthodox Jews are mainly in the Right, but if you go to the J-Street convention you will see many Kippot. The largest group there comes from Conservative and Reform families who are strongly connected to Judaism. They are young people who want a rich Jewish life filled with content and meaning, even if their life doesn’t look observant to you. In their twenties they are less connected to synagogues, but when they’re parents they’ll want to join a community suitable for them – and it is likely to be different than their parents’.”

Will they send their children to a school or synagogue with an Israeli flag in it?

“Sadly, there aren’t many ‘strong’ non-Orthodox schools. Again, the picture you’re painting of them caring only about ‘Tikkun Olam’ and nothing else Jewish that isn’t ‘anti-Israeli’ – is a caricaturization. True, compared to Bnei Akiva their children look different, but it isn’t fair to say they don’t seek a full Jewish life.”

I tell Beinart all the studies and polls show the young generation of American Jews is growing more assimulated, while losing its connection to Israel. He repeats his main argument, which to me only makes things worse: The anti-Israel activists are the Liberal Jews who care, the ones who were always more engaged, who participated in costly summer camps and arrived in Israel on Birthright. “Now they have an understandable anger towards Jewish educators,” Beinart says of the IfNotNow activists. “At Camp Ramah they try to create a Zionist identity without discussing the conflict at all – even if we put the Palestinian narrative to the side. They don’t give the children the most basic information you’ll get at an introductory university course on the Middle East. The result is young Jews arrive on campuses completely unprepared to deal with people from the other side who actually know things. They are angry about this.”

Would you be pleased if your children joined IfNotNow?

“Yes, I’d have no problem. It’s expressing emotion and opinion about what’s happening.”

Yet you still define yourself as ‘culturally Zionist.’ How are you willing for your children to be part of an anti-Zionist movement?

“From my perspective it’s not an anti-Zionist movement, but a movement that is not Zionist. I’d want my children to try and understand what that means. To me it is highly meaningful that there is a flourishing Jewish, liberal society in Israel. I would argue with the children on that point, but I have no problem with them fighting for Palestinians’ rights as a directive of their conscience, and I’d be pleased if they did it through a Jewish organization. For them it would be a way to understand we’re not only a tribe, but that we have a tradition of voicing our concern when ‘Jewish force’ is used against others.

It’s a shame that’s the only tradition we hear of from them.

“It’s the tradition they connect to.”

The Ground is Shaking

My conversation with Beinart puts me in a deeply pessimistic mood. At the end of the discussion I look at him and summarize it with three words: “It’s depressing.” Beinart laughs awkwardly. “Why are you depressed? What should I have said to not depress you?,” he asks, and I honestly don’t have an answer. “I think sometimes it’s hard to see things the way they are from here,” Beinart continues. “It’s also true for me: It’s hard for me to grasp how the world looks through the eyes of a different state or community. But it’s good that you’re trying to understand.”

At the other end of the American Zionist spectrum, Leibovitz is filled with optimism. His podcast episodes, he shares, have been downloaded more than 7 million times so far, and in his speaking tours with co-hosts he’s met Jews of all sorts. “Why has the podcast been so successful? Not because we’re smart or fun, but because Jews are seeking how to be together. They want a place to come to and just be Jewish. I don’t care if you keep Shabbat or not, or how you shave, just come sit with us. You’ll connect to us, because we’re all brothers.”

In the past, Leibovitz belonged to the Romemu congregation, which belongs to the relatively small denomination of Jewish Renewal – and deals with mystical and spiritual aspects of Jewish tradition, including ecstatic prayer and meditation. The synagogue actually operated out of a church, since its members couldn’t find another suitable location in the area. Today, he says, he no longer believes in the division of Judaism to denominations. “As far as I’m concerned,” he states, “there is only Jewish.”

What about those not looking to be together? Is American Jewry on the verge of splitting?

“We’ve already split. For those on the other side, the ‘Others,’ the benefit of your Jewish identity will lesson until it is no longer. Nathan Sharansky and Professor Gil Troy wrote an excellent piece for us in Tablet, titled The Un-Jews. They bring examples of Jews throughout history who believed in all sorts of additional agendas, such as those who supported Stalin as part of their Jewish identity. What happened to them? They’ve all disappeared from the map.”

What will happen to their look-alikes today?

“For the next five years they will continue to say ‘as a Jew I support Hamas,’ and then it will no longer interest anyone. The need for court Jews is short lived. I will say this with careful optimism: in the short term life will be very hard for American Jews, but in the long term we’re talking about a new golden age.”

Why will it be hard for Jews?

“If you belong to the 60-70% of non-Orthodox Jews, all the synagogues you used to attend have collapsed in front of the progressive cult, as have all the universities. I think what will happen here will force people to live active Jewish lives. They will understand it is not enough to go to services on Friday night, hear the sermon by the Rabbi at the end of the prayer, and then say ‘wow, that was an amazing sermon, now let’s drive home and eat dinner in front of Netflix,’; you need to create your own community life, to force yourself to understand what’s important, to connect to the sources. Many Jews on the progressive side feel their synagogue doesn’t provide relevant sources, and doesn't answer their needs. I see how such people start to study a text with a hevruta – study buddy – or go elsewhere for Kabbalat Shabbat. They feel the ground is shaking.”

“Understand: in my camp, in the ‘Us,’ there are connections we never thought were possible. At these meetings I see ultra-Orthodox Jews with Reform ones, conservatives with liberals. They understand they are here in the US together, fighting a frightening wave which threatens their communities. I am very optimistic about those Jewish seeking an alternative, the question is what happens to the passive Jews.”