Special: Leonard Cohen’s Secret Jewish Life

From Synagogue choir to electric guitar, from a Buddhist Monastery to a Jewish prayer book, from his millions of fans to the minyan present for his funeral. Shloshim (thirtieth day of mourning in Jewish tradition) of the death of Leonard Cohen, the soul singer who at the end of his life returned to the melodies of his grandfather

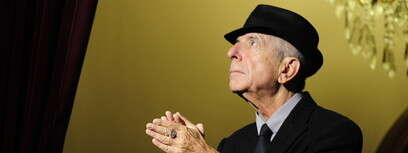

The brisk air of early winter blows between the rows of trees in the Jewish Section of the Mount Royal Cemetery in Montreal, Canada. Through the magnificent gate, embedded in a tall, stone wall, mourners slowly file in. Eliezer Ben Nissan HaCohen, better known as Leonard Cohen, was laid to rest in the presence of just a minyan of people.

The famous musician and songwriter passed away on a Monday in early November, while the world was preoccupied with the US presidential elections that were to take place the next day. It was only on Thursday, hours after he was buried in the city of his birth, that Cohen’s family released his death announcement.

Few were in on Cohen’s Jewish-Orthodox funeral plans, which were kept under a thick veil of secrecy. Two of those in on the secret were Adam Scheier, the Rabbi of the local synagogue Shaar Hashomayim that Cohen attended as a child, and Gideon Zelermyer, the synagogue’s cantor, who conducted the funeral service.

“It was small, personal service - just the bare minimum in terms of the ritual and the eulogies, no stardust,” said Zelermyer in a telephone interview from his home in Canada. “Leonard asked for a simple and plain service. We buried him in a pine coffin, without any of his fans, without a chorus, and without cameras. The family knew that if the news of his death got out, tens of thousands of people would show up.”

Around the grave were gathered Cohen’s children and grandchildren, two childhood friends and two representatives from the Jewish community – Rabbi Scheier and Cantor Zelermyer. “No one in the community knew about the funeral except for myself and the Rabbi,” continued Zelermyer. “It wasn’t difficult to keep it a secret, because when you understand the nature of your job, you respect people’s wishes and their privacy.” Cohen was buried in the same row as his parents, his grandparents, his great-grandfather and great-grandmother, who were all leaders in the Montreal Jewish community.

Cohen’s final burial requests did not surprise any of the people who knew him closely. Cohen’s private life, which he kept far from the spotlight, included prayer in the form of meditation at a synagogue, lighting the Shabbat candles on Friday night and even Kiddush and the blessing over the challah.

Cohen, 82-years-old at his death, was born in 1934 in Westmount, Quebec an English-speaking region of Montreal, into a middle-class Jewish Canadian family. His mother Masha Klonitsky was the daughter of Rabbi Shlomo Zalmen Klonitsky-Kline – a Rabbi, Talmudic scholar and linguist who served as the head of the Konvo yeshiva in Poland. Cohen mentioned his grandfather in various interviews, often speaking of his grandfather’s occupation with Hebrew words, to which he attributed his strong interest in literature and poetry.

His paternal grandfather, Leon Cohen, was the founder of the Jewish-Canadian Congress. Leonard’s father, Nathan Cohen, owned a clothing store and passed away when Leonard was just 9 years old, an event that affected him significantly. In his youth, Cohen studied at the Herzliah High School in Canada – a religious Jewish day school where boys and girls were taught separately – but later switched to the local secular Westmount High School.

The Orthodox Cohen family attended synagogue regularly at Shaar Hashomayim. Leonard remained in contact with the synagogue’s leaders until his death. Throughout his entire life, Cohen attributed great importance to the synagogue and Jewish community of his youth in the formation of his Jewish identity. During his final interview, which he gave to The New Yorker last September, he described the men in his family, specifically on his father’s side, as “the dons of Montreal”. Of his paternal grandfather, he said: “He was probably the most significant Jew in Canada.” “I have a deep tribal sense,” continued Cohen. “I grew up in a synagogue that my ancestors built, I sat in the third row.”

The Shaar Hashomayim synagogue is the oldest Ashkenazi synagogue in Canada and today it is the largest Orthodox synagogue in the country. The person who laid the corner stone for the building was none other than Leon, Cohen’s grandfather.

Befitting of a synagogue that gave birth to an international rock icon, Shaar Hashomayim takes the musical aspect of their service seriously, with a professional choir and cantor who accompany the prayers with the richest of harmonies.

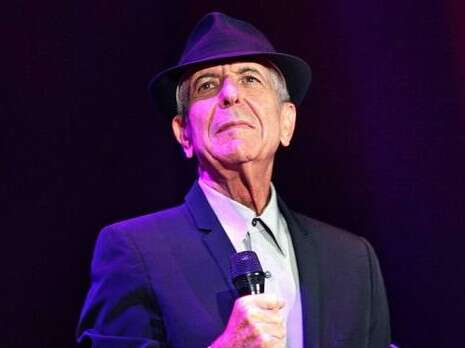

Zelermyer, who has been the synagogue’s cantor for 13 years, only met Cohen once just a few weeks before paying his respects to the singer during his intimate funeral at the Montreal cemetery. He had been in touch with the famous singer for nearly a decade before that, though. Just recently, he participated in the recording of Cohen’s final album, “You Want It Darker”, which the singer recorded together with the Shaar Hashomayim choir who contributed background vocals for two of the album’s songs. The prominent choral voices offer a strong Jewish backdrop with glimmers of Hebrew words, prayers and references to the Holocaust.

“The Cohen family was very connected to the synagogue, even before I got here,” he says. “Our relationship started after Leonard’s family sent him recordings of my singing with the Shaar Hashomayim choir. They told me that he just fell in love with the recordings and they suggested that I keep in touch with him. The thing is, that I didn’t really know how to keep in touch with a huge star like Leonard, so I waited until right before Rosh Hashanah and I wished him a good year,” he recalls. The relationship between the two became closer and Cohen even made sure that the Cantor and the Rabbi had seats to his sold-out concert. “Make sure that my Rabbi and Cantor get in,” he told his producers. The connection between the two became professional a year ago when Zelermyer received a surprising email. “He asked if I would be open to working with him on his new album.”

“I was shocked. I literally screamed. I woke my wife. She though something terrible had happened, but I calmed her down and told her that she had to read this email. I responded immediately and wrote, “Hallelujah! I’m your man!” (A reference to two of the singer’s songs – Ed.) There were a few more exchanges and he asked me to be in touch with his son Adam, who produced his final album.”

A day later, Zelermyer received a draft of the song “You Want It Darker” and he passed it on to the choirmaster and other friends who started working on the choir adaptation. Three weeks later, Cohen’s son Adam arrived in Montreal in order to play accompaniment for the recordings.

“Leonard wrote to me: ‘I’m looking for a melody that reminds me of the synagogue of my youth,’” says Zelermyer. For Cohen, who usually has female voices in the background of his songs, this was the first time that his accompaniment would be with men’s voices. “He wanted something different than what he had recorded up until that point in his life, something darker,” explained Zelermyer. “We tried to give the song a sort of religious feel because when you listen to the words, you find out that they contain a lot of religion. The sound of the Neilah prayer on Yom Kippur was an obvious choice.”

Before recording, the choir held rehearsals and later sent sample recordings to Adam as well as to Leonard who remained in Los Angeles and whose health was already declining. “We recorded a number of different versions, all in the synagogue’s main hall, since all of the other rooms were occupied,” recalls Zelermyer. “I sent him a photo of us singing in the synagogue and he wrote me back: ‘I have so many memories from the prayers from exactly that hall, it means so much to me that you, the Shaar Hashomayim choir, are participating in the project.’ It was important to him that his roots be part of the album, which in retrospect turned out to be his last.”

In addition to that song, the choir also took part in another song on the album – “It Seemed the Better Way”. “The idea was that since Leonard was a Cohen, we could integrate a violin solo of the Priestly blessing of the Holy Days and the festivals of Tishrei as an introduction and final riff for the song. It was a perfect fit. “

In addition to that suggestion, which came from the choir members, Zelermyer suggested adding a cantorial solo to the first song with the word Hineni (Hebrew for “Here I am”).

“We pass on our ideas and he really loved them. When we explained the Jewish background behind the concepts, he was even more enthusiastic.”

After many years of virtual communication, Cohen and Zelermyer finally met at the album’s launch, which was held at the Canadian consulate in Los Angeles. “It was the day after Yom Kippur. I was exhausted from the services and the fasting and Leonard said to me: “I’m so moved that you came, especially after Yom Kippur.” We didn’t have a lot of time together, but I gave him a gift – a machzor that we found in the synagogue that the community presented to his late sister Esther in 1945.”

Last Simchas Torah, right around the album release, the board of Shaar Hashomayim decided to hold a “Tribute to Eliezer” and integrate the tune of his song “Tower of Song” into the holiday prayers. After the holiday, Zelermayer sent the notes and lyrics to Cohen by email and a few hours later, the musician replied: “Chazak, chazak v’nitchazek” – “Be strong, be strong and may we be strengthened” – a statement of praise recited at the end of the reading of each of the five books of the Torah.

“The fact that Cohen knew the prayer from Simchas Torah

and not just from Shabbat or a major Holy Day like Rosh Hashanah, really amazed me. On the other hand, those are the Jews of Montreal: very traditional, even if they don’t keep all the Mitzvot,” says Zelermyer.

“Due to his involvement in the album, Zelermyer became a sort of messenger between the elders of the Montreal Jewish community and Cohen. “Everyone was suddenly asking me to pass on messages, everyone who was at his Bar Mitzvah or went to day school with him”. When the previous rabbi of the community, a 96-year-old, asked me to send regards to the famous alumnus, Cohen responded by email: ‘I can’t believe the Rabbi remembered me, I remember him as truly inspiring.’ He had a strong sentimental connection with the Jewish community in Montreal. Right before he passed away, Cohen was asked in an interview why he chose us, a synagogue choir. He responded: ‘When I was a boy, listening to the cantor and the choir were the only thing that I enjoyed at the synagogue which I was forced to attend.’”

When I try to understand from Zelermyer what he thinks about Cohen’s level of Jewish involvement, he quotes an interview that was held with one of Cohen’s friends after he died. “Leonard’s best friend visited him in Los Angeles, and the two decided to go out on a Friday night to a (non-Kosher –ed.) Korean restaurant. Leonard brought a sealed bag with him and when they reached the restaurant and sat down, Leonard pulled out a bottle of Manischewitz grape juice, a Kiddush cup and challahs. He recited the blessing over the wine, and the Motzi blessing over the bread, and then they ordered their food.”

Though Cohen was raised Jewish, in his 70s he discovered Buddhism and in the 90s was even officially certified as a Buddhist monk. Still, he continued to define himself as a Jew. “I’m not looking for a new religion, I’m perfectly happy with the old one, with Judaism,” said Cohen during an interview.

Regarding the puzzlement about how he combines between Judaism and Buddhist Zen, he responded: “First of all the Zen tradition that I practice has no worship or prayer and there is no recognition of god. So theologically there is no contradiction to the Jewish faith.”

Rabbi Mordecai Finley, who calls himself “Leonard Cohen’s Rabbi”, believes there is no contradiction between Cohen’s involvement in different religions and his Judaism. Finley has served as the rabbi of the Ohr HaTorah congregation in Los Angeles when Cohen was a member in his final years. “I officiated a wedding in Los Angeles and Leonard was there with his then-girlfriend, singer Anjani Thomas,” said Finley. “We spoke after the ceremony. They were very curious about me, we had an instant connection.”

Cohen, who was very popular in Canada and Israel, failed to achieve similar report in the United Sates, and Finley himself didn’t recognize him when they met for the first time at that wedding. His wife, Merav, who is Israel, who told him that Leonard Cohen had been one of her favorite singers in her youth and that he was one of the “greatest artists ever.” Finley added that Cohen himself was aware of his relative anonymity in the US, and even used to joke that “they could never arrest me in America, since they don’t know who I am”.

Finley received rabbinical certification from the Reform movement, but his synagogue was “Post-Orthodox, Neo-Hasidic”, according to his definition. Finley says that the congregation is on the spectrum between Reform and Conservative, “with Hasidic elements, spiritual psychology and Kabbalah”.

“We try to make it so that Judaism is relevant to people like Leonard. He was, in fact, attracted to us and we went on to have a personal relationship and meet regularly for Kabbalah study. We would meet on Saturdays and I would bring books from my library. We would also learn on the phone together occasionally if he couldn’t make it in,” continued Finley. “Leonard was a student of mine, how ever odd that sounds.”

“Anyone who asks that question doesn’t know Leonard. He was a Kabbalist. They would ask him if he believes in God – the question is moot, because when you’re into mystical things, God comes built-in. He may have been interested in other religions, but even the Rambam drew his greatest influences from people like Aristotle.”

He was a Buddhist monk and was involved in other religions, was he a Jew first and foremost?

“Of course. He was a Jew from the day he was born. And he didn’t leave Judaism for even a second through the day he died.”

So why did he delve so deep into other religions like Buddhism?

“He always maintained that Buddhism isn’t a religion. He called it a tuning fork that you can use to adjust yourself to better reach your goals. He told me that the years he spent in a Buddhist monastery were like a compass for his subconscious.”

Regarding the years he spent in India at that same Buddhist monastery, it has been said that in the tiny bungalow where Cohen lived, there was a coffee maker, an organ, a laptop computer and a menorah that was there to remind him where he came from.

Finley says that along with the study of Kabbalah, Cohen learned about other texts such as “Sfat Emet”. “We would study a page here and there, and then we would talk about it in depth. He would say to me, “Rabbi, let’s talk about your Dvar Torah from Shabbat,” or “What are we learning this week?”

How good was his Hebrew?

“He had basic reading skills in Hebrew, but not at a high enough level. He knew how to read text and understand it on a functional level, but he didn’t speak fluent Hebrew.”

The conservative Shabbat service at the Ohr HaTorah synagogue lasts just one hour, but Finley says that the Siddur wasn’t particularly relevant to Cohen. “For Leonard, praying with us was a form of meditation. I teach my students to meditate on one part of the service, to choose sections or sentences like “Ner Hashem Nishmat Adam” (which translates to “The flame of God is the soul of man” ) or Hodu l’Adonai ki tov, ki lay’olam chasdo (which translates to “Give thanks unto the Lord for He is good, for His mercy endures forever”). You don’t have to – and it’s not possible to – recite every line with intent, so at least connect to the lines that you do read. Leonard really connected to this method of meditational prayer. He would sit in a kind of state of meditation – he wouldn’t rock back and forth with a prayer book like many worshippers do. For him it was an opportunity to reflect.” Finley added, “Leonard had five or six verses he would memorize every Saturday. And he would come to me on Monday to learn the meaning of each and every word for his meditation. I guess that I was the first person to teach him meditation through the Psalms and the Jewish texts.”

The prayer at the Ohr HaTorah is decidedly different than the prayer that Cohen knew from his more traditional Jewish upbringing in Montreal. At the synagogue in Los Angeles, the prayers are sung to the tunes of Shlomo Carlebach and even modern Israeli melodies. “What attracted Leonard to our synagogue was, without a doubt, the music,” says Finley. “It’s obvious that our community is different than what he knew from Shaar Hashomayim, even though he really loved his community there. But in his adult life, especially near the end of his life, his Jewish home was neo-Chasidic. He wasn’t just committed to our synagogue; he was also committed to me. It still amazes me. He was a generous member of the synagogue,” he says, implying the singer’s significant monetary contributions to the community.

When I ask him if he was involved in Cohen’s final album, Finley responds that he wasn’t involved directly but says, “I believe that some of our discussions entered the texts in the album, the words there are very Jewish.”

This week, Finley will hold a ceremony to mark the shloshim of Leonard Cohen’s death. “Leonard wanted me to hold a memorial ceremony for him,” he says. Family and friends will be in attendance but the ceremony will not be open to the general public.

So how Jewish was Leonard Cohen? Maybe the person that can answer the question best is Prof. Ruth Weiss, a prominent Jewish intellectual in the United States. Weiss, who teaches at Harvard, met Cohen in 1954 when the two were young students at McGill University in Canada. “Leonard had always been different, or maybe a better word would be ‘special’,” she said in an interview from her home in the U.S. “He took the meaning of his last name, Cohen, and decided that it was his destiny. He always spoke as a member of the aristocracy of high priests, slightly archaic, about sacrificial offerings and about sins.” Weiss, who knew Cohen as a songwriter even before he became a famous singer, believes that his writing was influenced not only by Judaism but also from the significant interest he had always held in other religions. “Judaism came quite naturally to him on the one hand, but on the other hand it wasn’t natural because no University we studied at address the ‘Jews’. Judaism wasn’t mentioned in any lecture, there were no courses on Judaism, it made you feel like on the one hand, you’re free to be who you want but on the other, it doesn’t let you really be a Jew.”

Over the years, though, a conflict arose between the pair when Cohen declared to Weiss, who identifies with the American conservative right wing that “I feel more comfortable on a Greek island than in Israel.”

“I interpreted what he said to mean: ‘Do not expect me to be your Jewish ally’,” wrote Weiss in an article she published on the matter. “Cohen decided that he didn’t want to carry the burden of our community and its shabby, lonely culture. As far as he was concerned, he was the sole survivor. After I understood that not Leonard Cohen, nor anyone else from my generation, would tell the truth of my generation, I started to write.”

The things he said about Israel came after his visit to the country and performed for soldiers in Sinai during the Yom Kippur war. He performed in Israel on other occasions – in 1972, when he came down with an attack of stage fright and returned to the stage only after the audience broke out in song singing “Hevenu Shalom Alechem”. In 2009, during a tour he did due to financial difficulties he was experiencing, he was received in Israel as a national hero and finished the mythological concert in Ramat Gan with the Priestly Blessing over the crowd.

In an article she wrote after his death in the online magazine “Mosaic”, Weiss says that maybe she was wrong about Cohen’s commitment to Judaism but says that she still believes that he didn’t live an entirely Jewish life.

“Yes, it’s true. Listen, he turned Judaism into something that fit who he was, and what he felt. Leonard wasn’t one to do something he didn’t believe in entirely, and in the same manner he was also independent in his Judaism. My Judaism is expressed in my commitment to it, but for Leonard it was different. He saw himself as an orphan. Judaism maybe owed him something, but he didn’t owe Judaism a thing.”

î÷åø øàùåï áîáöò äéëøåú. äøùîå ì÷áìú äöòä àèø÷èéáéú » äéëðñå ìòîåã äôééñáå÷ äçãù ùì nrg