Jewish Cowboys: The Story of the First Jewish Town in the Wild West

Native Americans instead of Arabs, bears instead of malaria-carrying mosquitos, and shady gun-slinging entrepreneurs instead of the Baron Rothschild: while the first pioneers tried to settle in the Land of Israel, a Hebrew homeland was founded in the Wild West, too

COLORADO, AUTUMN OF 2016. The temperature drops further and further as the car climbs westward along route 50. Out in the distance, the snowy peaks of the far off mountains jut out from the horizon. As we get further from the settled plains of the big cities of Denver and Colorado Springs, the scenery changes, becoming mountainous, wooded, even Biblical.

Beyond Canon City, the road becomes narrow and tortuous; our path runs parallel to the Arkansas River that flows beside the road. Even with the windows rolled up, it is impossible to miss the thunderous rapids of the water rolling eastward, down into the valley.

The area is only sparsely populated. 60 barren miles separate Canon City from Salida, the next major town. Between the two, the road is dotted with small inns, gas stations with convenience stores, here and there a farm. We pull up to one of these convenience stores, but for us, this is not a pit stop. It’s our destination.

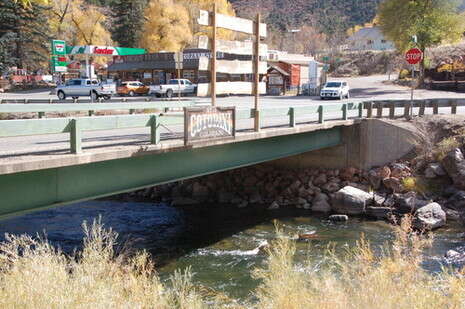

Welcome to Cotopaxi. Today, the town is neglected. Population: just 47 souls, according to the last census. Most of the residents work in the rafting industry, which is bustling in the summer months. In the fall, there are far fewer visitors, barely a minyan (Translator’s Note: 12 people needed to hold group prayers in Jewish tradition). Jeff, the owner and head salesman at the local store, which is, of course, adjacent to the gas station, is surprised when we ask about Cotopaxi. “Listen,” he says in a booming accent. “The only people who stop here are people lookin’ for a restroom. What exactly are you lookin’ for?”

Well, I am looking for my people. I am looking for the 63 Jews who, 143 years ago, established a Jewish town here, with the supreme sacrifice and genuine effort trying to make their way from destitute, frightened European refugees to become proud American farmers who could live off the land. Sixty-three men, women and children, who over the course of two brave years managed to create a new facade of the Jewish cowboy, standing tall and courageous – until their strength could hold on no longer.

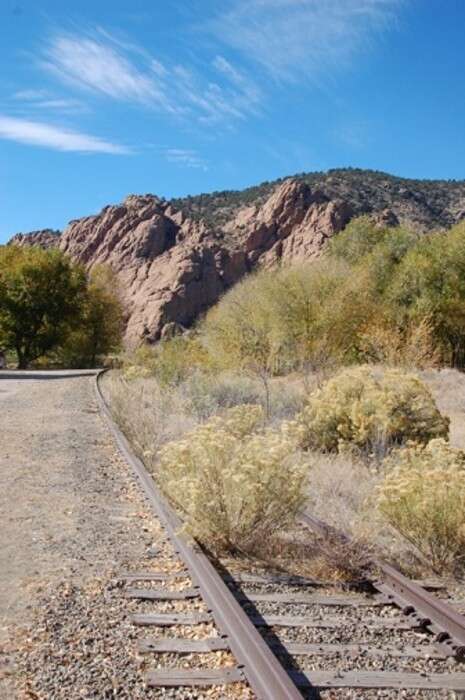

Jeff looks at me and smiles. “Oh yeah. The Jews that built this place. We all owe them quite a bit. Okay, maybe not that much, but we owe them. That’s for sure. I feel bad telling you this, but the only remnant you’re going to find of them today in Cotopaxi is their cemetery. Cross over the river and the abandoned train tracks. Pass the post office and keep going for a mile and a half through the woods. You’ll see it.”

In the early hours of May 9th, 1882, the sound of the train’s horn traveled through Cotopaxi, which was then a small town that almost did not exist at all. The iron beast rolled slowly into the station and it took a few minutes even after the screeching sound of the breaks died down for the tranquility and peace to once again settle upon the valley.

The few residents of the town, which had been established less than a decade earlier by the explorer and researcher Henry Thomas, gathered on the wooden platform in order to see the oddity that might step out of the shiny cars at any moment. And there they were – off the train stepped fifty people who had come there to stay. It was at that moment that the all-too-short story of the Jewish Wild West began.

In hindsight, the first minutes on the platform were an eerie foreshadowing of the bitter end to our story. The locals – rugged miners and cowboys – were terribly disappointed when they saw the bizarre foreigners that had arrived. They did not speak English and they certainly did not seem to be strong farmers who might invigorate the cold, rocky soil.

Political correctness did not yet exist in America and the travel-tired Jewish newcomers who had spent five days on a train from New York were received with cold stares and frigid contempt. But in comparison with where they had come from, angry stares were nearly as good as a welcome parade.

One year earlier, in March of 1881, Czar Alexander the Second had been assassinated setting off violent riots against the Jews in the southwestern region of Russia (which today is known as Ukraine). Many of the Jews did not have to wait for the riots to reach their doorstep to understand that their relationship with Mother Russia was over, and the once slow emigration from the region became a race to escape.

In the coming years, until World War I broke out, 2.5 million Jews would leave Russia. Of them, 2 million came to the United States in search of a new life. They landed on the east coast, where most of them would remain. Manhattan’s Lower East Side was teeming with Russian Jews.

And it was there in Manhattan, in the stale cellar of an old building, that a young, idealistic Jewish man by the name of Michael Halperin would try to fulfill his vision. He believed that the Jewish people had an inherent connection to the soil. He believed that the Jewish newcomers must disperse throughout the country and submit themselves to manual labor in order to eke out a living. But over the years, he was a lone voice in the wilderness. The Russian Jews continued to hold tight to New York, refusing to budge.

Halperin had all but given up, until one night, when a man named Jacob Milstein knocked on his door. He was the nephew of Saul Baer Milstein; a wealthy Jewish businessman in Russia involved the establishment of Jewish settlements there. Because of his experience rubbing elbows with the Russian government, Milstein the Uncle quickly recognized that the Jewish future in Russia was not particularly promising.

Even before the pogroms began, Saul Baer Milstein understood that in order to protect his extended family – and no less importantly, his extensive wealth – he would have to find a new place to settle his clan. As early as 1878, Saul sent his nephew Jacob to America, giving him one simple task: Jacob was to search the land and find out if the rumors were true. Was America really a land of plenty? Free of anti-Semitism? Rich with business opportunities?

The young Milstein came to America, casually exploring the country and living comfortably on the generous allowance his uncle sent each and every month. And then the nephew made a grave error. Back in Russia, Jacob and Saul Baer’s eldest daughter, Nettie, were secret lovers. Now, an ocean away from his sweetheart, Jacob yearned for her. So he convinced her to leave her father’s house and sail to America to live with him.

Saul Baer was furious. He failed to convince his daughter to return, but got his revenge by cutting off his nephew’s monthly allowance. Jacob had no choice but to enter hard labor. While working in a metal factory with limited safety measures, he lost his eye. So when he came to Halperin’s office he was desperately looking for a way to smooth things over with his father-in-law.

It was around the same time that Halperin began to receive correspondence from a man named Emmanuel Shaaltiel. Shaaltiel was an officer in the Confederate army during the Civil War (1865-1861) and when the South saw defeat, Shaltiel immediately moved to the north, volunteered for the Union army and even took part in a number of battles against the Indians. It was during one of his tours that he came upon the mines adjacent to Cotopaxi. Soon after, Shaaltiel purchased the town and the roughly 2,000 acres that surrounded it. He decided that the town would be called Shaaltiel, a name that, for some reason, failed to catch on.

Cotopaxi got its name because its founder, Henry Thomas, who settled the region in 1871, believed that the area looked similar to the volcano of the same name in Ecuador. Thomas was shot and killed a few years later on the steps of the store that was, incidentally, owned by Shaaltiel, but the name he gave the town remains to this day.

During the flood of Jewish immigrants from Russia, Shaaltiel ran into a serious problem: not far from the Cotopaxi mines, new mines with real potential were discovered, and the salary offered to the workers there was much higher than what he was willing to pay.

As a result, his mines remained unmanned and there were rumors roaming through the Colorado hills, reaching as far as Denver, that Shaaltiel was not paying his workers on time and that the workers were bouncing between strikes and total despair. So Shaaltiel had an idea: he would bring in fresh labor – the cheapest he could find – the hands of his very own people fresh off the boat from Eastern Europe.

In his letters to Halperin, Shaaltiel could not have spoken more favorably about the wonders of Cotopaxi: the fertile soil, the fresh air and the great employment opportunities. To sweeten the deal, he even promised any newcomer to the town everything they might need for the first few years until they got properly settled. Shaaltiel exalted the new law, which was intended to promote migration westward, promising each and every settler a plot of 160 acres, free of charge. They could use the land to grow crops or raise livestock. All they had to do was come.

It was just one day after their feet hit the boulder-laden soil of the Rockies that the Jews of Cotopaxi began to comprehend what they had fallen into. Julius Shwartz, Halperin’s representative in the area, showed the newcomers the plots of land they had been promised. And they were shocked.

The plots were rocky and steep, not suitable for growing anything, and most of them were located several miles from the town. The next morning, they surrounded Schwartz, demanding an explanation. Shaaltiel did not hesitate, sending in armed guards to protect his hapless representative from the angry mob, who refused to calm down.

The land was not the only problem. Of the 22 homes that Shaaltiel had promised the new settlers, just 12 were standing. The homes that had been built were missing the most basic amenities. Some didn’t even have windows. Despite it all, at that point in time, the pioneers still managed to be optimistic, making a real effort to put down roots. They leased better pieces of land from local residents, land where they could sow corn and potatoes. The arrival of 13 more Jews, among them a butcher and a Hebrew teacher, lifted the spirits of the community’s members.

On Friday, June 23, 1882, a procession was held for the first Cotopaxi Torah scroll. That Torah was the first and most important thing that the community had requested from Halperin’s office in New York, and the excitement that came with its arrival was palpable. Since every Jew in the town was religious, they decided to sacrifice one of the houses intended to be used as residential space, and converted it instead into a synagogue. The Torah portion Chukat was the first one ever read in Cotopaxi, and likely the first one ever read in America’s Wild West.

The next few months, before the harsh western winter set in, were the Golden Age for Cotopaxi. Two weddings were held at the synagogue, and despite the many difficulties they faced, it seemed that the settlers were adapting to their new home, by no small measure thanks to their neighbors – themselves farmers with German roots. The Jews managed to communicate with them in Yiddish, trading with them to get necessary supplies. Julius Shwartz sent word back to Halperin’s office in New York describing the idyllic harmony.

But the fall of 1882 brought crisis. The corn that had been planted four months earlier withered and the potatoes were destroyed by a sudden frost that swept through the valley. The Jewish farmers had hoped that the revenue from their first harvest would cover the credit they had taken out at the local store, which, of course, was also owned by Shaaltiel. They had no choice but to incur further debt to survive.

Shaaltiel in turn, relied on Halperin, who made sure that the HEAS (Hebrew Emigrant Aid Society) would cover the settlers’ expenses. But when it became apparent that New York was not sending any more money, Shaaltiel’s attitude toward the settlers grew hostile. He cut off their credit and accusations began to fly.

As winter settle in, three babies in the tiny Jewish community died. Rabbi David Gropitzky’s toddler son died from an infection that raged through his body after the child stepped on a rusty nail. He was buried in a small flat plot just north of town. Adjacent to him was buried the daughter of Shlomo and Rachel Chotoren and the son of Joseph and Anna Nudelman, who died just a few weeks apart.

During that same winter, the Jewish settlers were forced to deal with an array of challenges, each of which had the power eliminate the weak. In addition to the terrible conditions in the bitter cold of the Rockies, the town was raided by Indians and its settlers had more than one unfortunate encounter with a hungry bear in search of food. But despite their hardships, they stuck together and prayed for the arrival of spring.

Spring did arrive, and with it, the first Passover. The atmosphere was festive. Flour for matzos was brought in especially from Denver and despite the hardships and mourning for the three small children who had passed away, optimism once again swept through Cotopaxi. But another frost came through killing their second harvest. From conversations with the neighbors it became clear that the Rocky Mountain soil permitted just one crop cycle per year and not three, as they were promised.

At that point, the Jews of Cotopaxi understood that while they might have been brought there under the pretense that they would make their livings as farmers, they were actually to serve as cheap labor in the mines. The fields were abandoned one after another and their owners went to work outside the town’s limits. Most found work with the railroad company, which paid them wages of three dollars per day.

The relationship between the settlers and Shaaltiel, which was already rocky, was now on thin ice. They blamed him for failing to honor their agreements with him; they accused him of fraud. He blamed them of using their Jewish laziness that they had brought with them from Eastern Europe; he accused them of wasting their resources on religious ceremonies, celebrations and idle days rather than working hard and investing in the soil they were there to cultivate.

When the next winter settled in, times were desperate. The settlers didn’t have enough money to stay warm. The women would stand beside the train tracks to collect pieces of coal that had fallen from the locomotives and hurry home to warm themselves in the bitter cold.

The rumors about the dire state of Cotopaxi reached the Jewish community in Denver, who rushed to send three representatives to the desolate town. In February of 1883, the three visitors presented a report they had put together. They placed the blame entirely on Shaaltiel.

According to the report, the lands that he divvied up amongst the residents were of no value. They also noted the dissonance between his promises of shelter and the reality there, and even hinted that he had lined his own pockets with the funds that had been sent from New York to support the newcomers. The bottom line of the report was unequivocal. Cotopaxi had to be evacuated immediately.

Indeed, most of the Jewish settlers left the town even before winter’s end. Six particularly brave families remained for one more season, trying in vain to dig deep in the frozen ground and hold onto the dream of being the Jewish American Cowboys just a little bit longer. In June of 1884, after the third year of failed harvest, Cotopaxi was abandoned by all of its remaining Jews.

Most of the original settlers remained in the Western United States, some joined the Jewish community in Denver, and others continued further. Jacob Milstein made amends with his father-in-law, and together they built a huge cattle farm next to Boulder, Colorado where the family lived for decades.

And Shaaltiel? He continued trying his hand at a variety of business ventures. The most reliable evidence indicates that he died in Wyoming, a few years after the Cotopaxi venture, and was buried in an unmarked grave.

The entrance to the cemetery of Cotopaxi does not reflect all that it contains. A large cross adorns the gate, and amongst the grass and the lonely trees are scattered roughly a dozen cross-laden graves. But at the edge of the cemetery is a small, fenced-in area, adorned with a distinct, seven-armed lamp and a little sign that tells the story of the Jews of Cotopaxi.

Your eyes are drawn down to a chiseled grey stone, below which is the shared grave of the three children who died back in the harsh winter of 1882. At some point, a passerby added a Star of David made of stones, which has since been engulfed by grass.

After reading a number of psalms and clearing weeds from the grave, we walk back towards the town. The train tracks, no longer in use, are covered in thorn bushes and thistles. Adjacent to the tracks flows the Arkansas River as it has for generations seemingly the only living thing in this corner of the world.

The little shop in Cotopaxi sells a few souvenirs. One shirt reads, “If idiots could fly, Cotopaxi would be their airport”. When I asked about the odd, self-deprecating humor, Jeff answers with resigned smile: “The place is pretty remote and pathetic, so we don’t have much left but to laugh at ourselves a little.”

Just before we turn around and go back through the Colorado planes to civilization, it is impossible not to try and imagine the town as a large, bustling, Jewish metropolis out there in the Rocky Mountains. Maybe, if the circumstances had been different, or with better leadership, the outcome would have been better. These kinds of theoretical questions can be hard to answer. But if you lift your eyes and look out across America in the late 19th century, it becomes clear that Cotopaxi was not alone.

At least eight more towns and Jewish agricultural settlements were established in those years. They were all inhabited by immigrants fresh off the boat from Russia, and every last one of them failed and faded within a few short moths, surviving a few years at most.

The longest and most significant venture was in the state of Oregon. A few dozen members of Ahm Olam, a movement established in Russia as the pogroms swept the region in 1881 which made it their mission to support Jewish agricultural communities in America, placed the corner stone for New Odessa in 1882.

The cooperative colony managed to survive until 1887, likely thanks to the agricultural preparation granted to the group’s members. But examination of the origins of New Odessa reveals many extensive similarities with the problems and issues that characterized Cotopaxi: poor management, unrealistic expectations that were quickly shattered on the rocky soil, quarreling and internal disputes that did not cease for a moment. All that remained of the colony and from the grand vision of Am Olam was reduced to a co-op laundry that the members of the movement ran together in San Francisco, and that too was shut down four years after the settlement failed.

Another Jewish agricultural effort, also the product of the Am Olam movement, was established in South Dakota. The place was called Bethlehem Judea, and 32 Jews worked the land in the hope that it would attract many others. Adjacent, to it was established the settlement of Cremieux. Herman Rosenthal, the founder of the settlement, had already tasted defeat a year earlier when he established the first Jewish agricultural colony, Sicily Island. It fell apart within three months, and you can probably already guess the circumstances surrounding its fall – the soil was poor, the weather was nightmarish, and the disputes among the members were never ending.

After that bitter experience, Rosenthal arrived in South Dakota, determined not to repeat the mistakes from Louisiana. But he failed once again. The cooperative method was unsuited for American culture that the colonists worked so hard to assimilate into, Cremieux and Bethlehem fought amongst themselves over resources and manpower and both caved quickly.

A similar but slightly different story was that of the last two Jewish agricultural colonies established in the United States -- this time in New Jersey. The first was Carmel, founded in 1889 and the second was Woodbine, founded in 1891. Though the two did not fall to pieces, they also did not remain Jewish towns; their placement adjacent to large towns resulted in their being swallowed up and turned into American suburbs with no reminder of their Jewish or agricultural origins.

A number of researchers made an effort to find an answer to the question of why it was that the American Jewish agricultural efforts were such a miserable failure, while during the same period, and typically under more difficult conditions, the Jewish Israeli culture in Palestine managed to take root. Professor Margelit Shilo, a historian, published an article a few years ago that compared the first Jewish agricultural colony in the United States, Sicily Island, with Rishon L’Tzion, which was established in 1882.

settlements in the country as well. That is as opposed to the slower progress in the Land of Israel at the time, which had yet to see any major urbanization, making it easier to continue developing agriculture.

But in the end, Prof. Shilo reminds us not to ignore the nationalistic aspect – which of course existed in Israel, but less so in America: “At the center of the lives of the people from Rishon L’Tzion was the establishment of a Jewish national entity. In contrast however, the founders of the first Jewish-Russian colony in the U.S. voted for a national objective during the planning stage but it did not serve as their compass and did not remain a central motif in their lives after the colony was established.”

In other words, if instead of the snowy peaks of the Rocky Mountains, Cotopaxi had been nestled in the hills of the Upper Galilee, it is entirely possible that we would have a Wild West town that would still be alive and kicking today in a valley hidden somewhere between Carmiel and Safed.

מקור ראשון במבצע היכרות. הרשמו לקבלת הצעה אטרקטיבית » היכנסו לעמוד הפייסבוק החדש של nrg